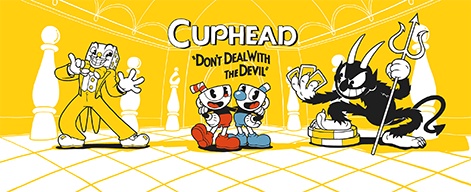

In the indie boom of the last five or so years, there have been instances of people who were totally new to games development seeing massive success on their first go. But it's hard to think of projects that were as successful as Cuphead. Released in September 2017, the game sold more than two million copies before the end fo the year.

We caught up with studio co-founder Chad Moldenhauer to find out how this game came together and why it was such a smash hit.

So, take us back to the start. What was the initial napkin idea behind Cuphead?

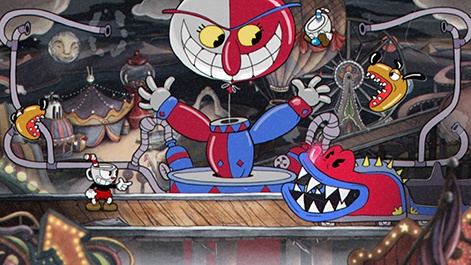

Cuphead always started as more of us asking: 'What kind of game do we want to make?' – without any concern about the visuals or audio side of things. A lot of people when they first started talking to us were saying: 'It's so cool that you planned the game visually with all that 1930-era inspired ideas before you thought of the gameplay', but it was definitely the opposite of that. My brother [Jared Moldenhauer] and I knew we wanted to make a game and we chose to make a game that we could wake up and love working on day-in and day-out. We had this idea where we wanted to make a game that's way more focused on bosses and just went from there. It was originally planned to be around the eight-to-10 bosses in the game and as the game got more attention we went back to our original dream scope. We had all these cool ideas but when we first started it was just a three-man team so we were mature and decided to make a smaller project initially.

Did the team grow alongside the amount of attention Cuphead was receiving?

It kept growing in scope by reaching into our original dream. We never thought in a million years we could make a game exactly like we wanted. But as the game got more press and as we got deeper into development, we kept adding in bosses and knowing it would work within the smaller scope, bringing in the weapon shop was a cool idea. It got to the point where we said we could bring everything back in and the team scaled up as we made the scope much bigger.

Was there ever a concern that you might have made the game too big for the team you had?

Maybe not too big, but a little bit of: 'Wow, how much did we just bite off?'. We're already in it, we've put in so much time and effort into all these different areas of the game and there's still a lot left as we're looking at it. Since we loved the project so much, it wasn't really negative, but it definitely kept us on our toes to really sober us when we'd look at a larger picture of what was left to finish. Especially with this being our first game, we didn't have the ultimate time budgeting senses. If we started a certain boss or level, we'd calculate it out to our best guess, then we'd multiply that by two and thought that would be an amazing estimate of time what we'd need, but it turns out we were wrong most of the time. Hence the delays.

It seems there was a lot of risk riding on Cuphead - you even remortgaged your homes to pay for the game's development.

When we got to that point, there had already been a bunch of baby steps leading up to that. We didn't say: "Okay, we're going to make a game, let's mortgage our homes and go all-in". We started part time and then got a little bit braver, hired a few more people. It wasn't until 2015's E3 with the stage presentation and the trailer and all the stuff around that event before we sat down to say: 'Listen, there's way more press and way more fans than we could ever dream of – this is a much bigger game than we initially thought. Maybe we should become really serious about that'. There was already so much on the side that's showing us that even if we went all-in so to speak, we should be able to break even. Sure, it was a risk, but we weren't just taking a blind risk.

The game launched in September and has sold more than two million copies. What's that experience been like for you?

Jared and I thought eventually if we could hit one million, that would be a really awesome milestone. Maybe it'll take us two years, maybe it'll take longer, shorter, but around the one million mark would be mindblowing. Two million sales, we thought over the years the game would go on sale, would be much cheaper, there was a hope that we could reach that, but the fact we hit it before the year ended is to the point where I don't think we can fathom what's happened. It still seems very surreal. It's amazing and we love it. It means we can continue to make games and there is a market for hand-drawn animation and video games. But at the same time, it's hard to process, in a good way thought.

Why do you think the game has sold so well? What about it speaks to two million-plus people?

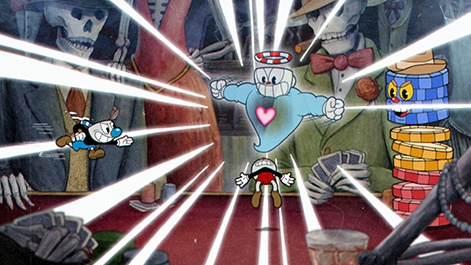

Looking back on it, I think we can pinpoint some of the reasons. Not just because we can look at the game and say: 'Oh, we definitely know that these are the major points', but after reading reviews and talking to fans and getting this overall cloud of feedback, we can kind of pinpoint areas. Of course, the hand-drawn art and the 24 frames per second animation hasn't been done in a video game since Dragon's Lair.

Then, our attention to detail was a factor. Not just making the fact match the 30s era – we went full on. The entire soundtrack was made in the same way, the backgrounds, the watercolour paintings, the physical 3D models that we were made for the game. We were really picky about all the aesthetic and the overall soul of the game. That resonated well with a lot of people. I think, at least I'm hoping, when people play Cuphead, they can tell that there was a lot of crazy and passionate people pouring their hearts as we made this game. That's on the visual and audio side. On the gameplay side, the style of games that Jared and I grew up playing in the late 80s and early 90s were all very challenging but extremely fair. The controls themselves weren't too hard, they were more basic, but the game itself required you to master the controls to become a better player.

We're strong believers in that if you have a little bit of business sense and you pour your hearts into a project and only focus on it we hope that at least a fraction of success should follow. When we set out to make Cuphead, our main dream was to earn enough money to make one more game. We weren't doing any focus testing to make sure we were hitting different crowds of people so that we could have these magical earnings. It was about making a game that we really love and being really picky about all the details in the game and send it out into the world. I should also mention that Microsoft has been a key partner in all of this. The fact they had been pushing us at so many trade shows and advertising with Cuphead and really pushing us out there has helped us tremendously.

What lessons have you taken away from Cuphead's development?

Since we have never made a game before, every day was a new lesson. We started the project much slower, only working on weekends, then it was taking a day off our real jobs so that we could work a full day and the weekend, and slowly ramping up the team, we never hit any massive road blocks or had to learn any huge, huge lessons because we ramped up at this not perfect but semi-perfect pace which meant we could fumble and fall at the very small minor issues and not walk away with any big: 'Oh, we wasted a year doing this and I'm glad we learnt that now'. It was more three days would go by and we would say we're doing this way too slow and need to figure out how to make our pipeline, for instance, move much faster. Then we'd huddle for a couple of days and fix that area. When you start really small, everyone working on a project knows every single part of the project. The core, especially the core processes to build a game, was always refined and we sped them up as much as we could over the first few years, that when we really started to go full swing into production with a larger team. It wasn't seamless, but it worked for what kind of a game this is. The key is, and we've heard this a lot even when we first started, that people who in indie or triple-A say if you want to make a game, make something small, release it, then make your next game and keep doing that and you'll learn lessons along the way. We pretty much did that within one game.

When the game launched, there were articles that pointed out the racial connotations inherent to the 1930s art style that Cuphead uses. How do you respond to that commentary?

We've always taken the stance that we're fully against all the racism of the era, we're not trying to embrace any of that. We just wanted to us the aesthetic and art that was made at that time. We intentionally stayed away from all of that because we weren't trying to recreate the era or make a statement about the era – we just loved the art style and that's the only thing we took out of it.

What's next for Studio MDHR?

We've finally climbed out of the launch and the majority of the bigger patching that we had to do. Starting today, we're jumping on calls and planning what we're going to do next. We have some very high-level plans but we're not going to start talking about what they are because when they are at a high level, lots of them get cut. If you mention something, people will go: 'That's the coolest thing that you are going to make', then we decide to cut it and you have a bunch of people angry at you for something that never existed. We like the idea of planning internally, and when we know and are happy with what's coming up, then we'll share with our fans.